Hello and Welcome to Office Hours. I’m your host, José Olivarez.

Today, I am starting a new series. Inspired by conversations with my friend, Traci Thomas, and conversations with students all over the country, I will be sharing poems I enjoy alongside a few meditations about how I read those poems.

I understand that the idea of reading poetry can make people anxious. When I made the leap from only encountering poems at performances (poetry slams and open mics) to grabbing random books of poetry at my library, I was terrified. I couldn’t make heads or tails out of the poems in the books. I didn’t get them, with rare exceptions.

I still encounter poems that I’m not sure I get, but those poems no longer frighten me. I now view those poems as opportunities for learning and discovery. Frankly, I rarely care about what a poem means. Poems are not math problems, I tell students when they share their anxieties about poetry. They don’t have right or wrong answers. That doesn’t make my students any less anxious. It would be easier if there were right answers to discover. Nevertheless, I try to guide them back to the uncertainty a poem can present us and the gift of that uncertainty. What images excite you? Is there a piece of language that startles you—that doesn’t make sense— that is counterintuitive? There, I ask them to dig in. Why does it surprise you? What does it make you feel?

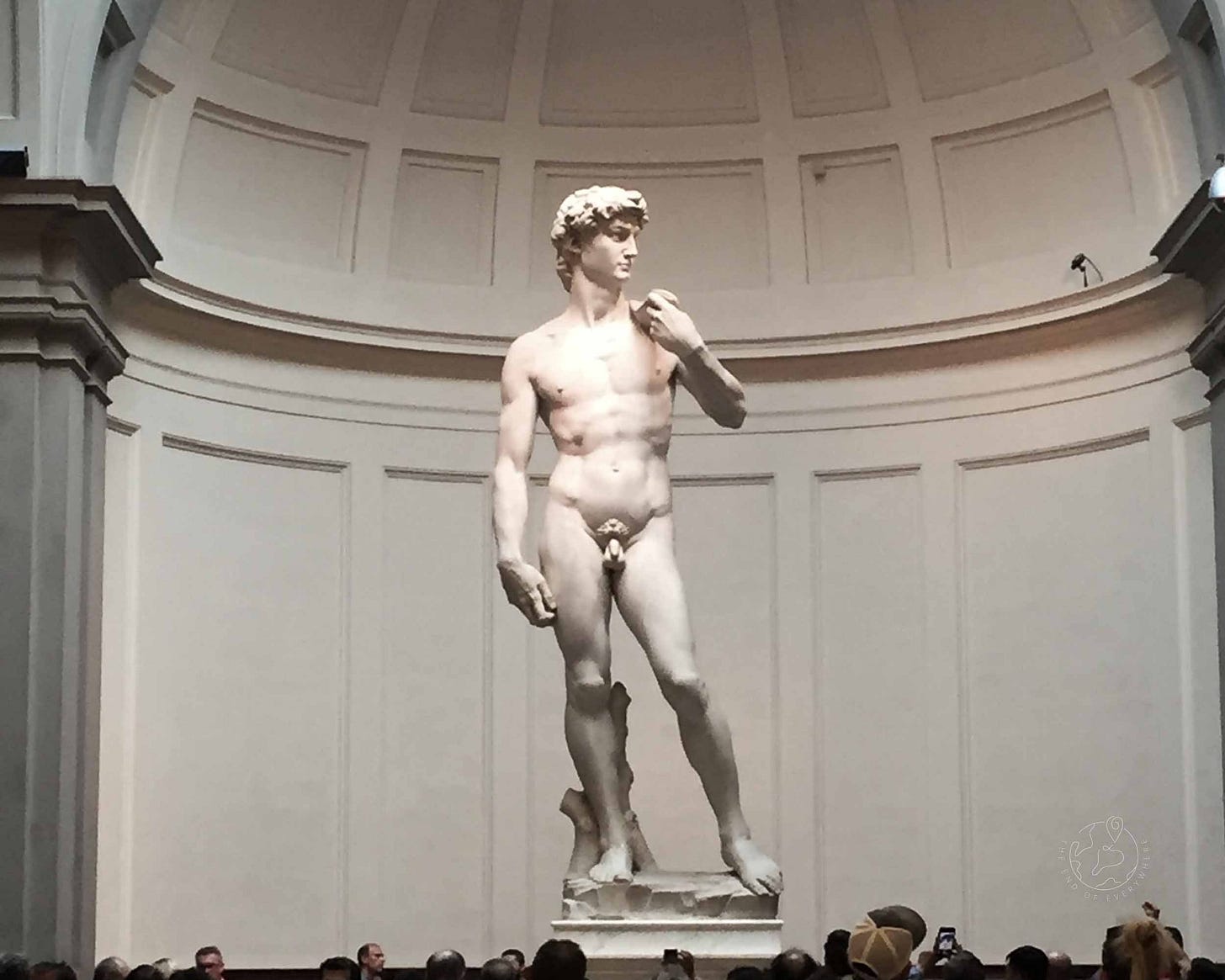

Poetry is not math. I think about poetry as being akin to sculptures. There are sculptures that immediately make sense to me. I understand a sculpture like the sculpture of David.

But there are sculptures like The Chicago Picasso that are a little bit more inscrutable. What do I make of this:

Perhaps there is a face? Perhaps there are wings? Perhaps there is hair? A ribcage? A body? Is it human? Is it an animal?

I don’t know, but I can appreciate the craft. I can spend time with the sculpture and appreciate its design. I do not need to abandon my looking just because I don’t fully understand it. In fact, I can enjoy the feeling of wonder. Like looking at a cloud and seeing different objects depending on my mood.

If you are someone that is scared of poetry: Welcome. I hope this series will encourage you to read more poems and to appreciate them even when you don’t always understand them.

Today’s poem is The Forgotten Dialect of The Heart by Jack Gilbert.

The Forgotten Dialect of The Heart

by Jack Gilbert

How astonishing it is that language can almost mean,

and frightening that it does not quite. Love, we say,

God, we say, Rome and Michiko, we write, and the words

get it all wrong. We say bread and it means according

to which nation. French has no word for home,

and we have no word for strict pleasure. A people

in northern India is dying out because their ancient

tongue has no words for endearment. I dream of lost

vocabularies that might express some of what

we no longer can. Maybe the Etruscan texts would

finally explain why the couples on their tombs

are smiling. And maybe not. When the thousands

of mysterious Sumerian tablets were translated,

they seemed to be business records. But what if they

are poems or psalms? My joy is the same as twelve

Ethiopian goats standing silent in the morning light.

O Lord, thou art slabs of salt and ingots of copper,

as grand as ripe barley lithe under the wind’s labor.

Her breasts are six white oxen loaded with bolts

of long-fibered Egyptian cotton. My love is a hundred

pitchers of honey. Shiploads of thuya are what

my body wants to say to your body. Giraffes are this

desire in the dark. Perhaps the spiral Minoan script

is not language but a map. What we feel most has

no name but amber, archers, cinnamon, horses, and birds.

When I read this poem, I begin with the first sentence spread over a line and a half. “How astonishing it is that language can almost mean/ and frightening that it does not quite.”

This is it. The crux of the problem with communication. We can only ever make gestures at what we really mean, but no matter how precise our language is the person on the other end of our communication may interpret it differently than we intended.

Gilbert continues: “Love, we say,/ God, we say, Rome and Michiko, we write, and the words/ get it all wrong.”

Perhaps the reference to “Rome and Michiko” frightens you because you don’t understand it. You can look it up. Or you can ignore it for now: Love, we say, God, we say, and the words/ get it all wrong.” Language is the best we have. We try so hard to name our feelings. And yet, the words get it all wrong. Think about the word “love.” It is the best word we have for that overwhelming feeling of devotion and care and romantic desire towards another person. But how can the word “love” be enough when we use the same word for all our different loves and the same word for a good pop song or a good sandwich? Clearly, the word “love” is not nearly precise enough to mean what we intend for it to mean.

My favorite part of the poem is when Gilbert starts making metaphors for emotional language: “My joy is the same as twelve/ Ethiopian goats standing silent in the morning light.”

Not thirteen Ethiopian goats. Not eleven Ethiopian goats. Twelve. My joy is the same as twelve Ethiopian goats standing silent in the morning light. I love those lines. In giving shape to my joy, I would not come up with goats. And yet, when I read this poem, I am nodding alongside the author. Yes, joy is twelve Ethiopian goats standing silent in the morning light. This also makes a great warm up exercise: What is your joy today? My joy is two masked luchadors waiting for the bell to ring. My joy is a wolf napping in the sunlight. My joy is a library full of books. My joy is a basketball court at dawn. My joy is a ripe avocado. My joy is twelve Ethiopian goats standing silent in the morning light.

How do you know when an image is precise enough? How do you know if you overwrote an image? If I say my joy is an unopened pack of Pokemon cards at recess, is that enough? Is it a better image than: My joy is an unopened pack of Pokemon cards? Ultimately, one of the joys of writing poems is seeing what you can get away with. Seeing how far readers will follow you.

My favorite image in the poem is “Giraffes are this/ desire in the dark.” What?! What does it mean? I don’t know, but I love it. It feels right. It transforms my understanding of giraffes. It makes them feel more sensual. Giraffes are this/ desire in the dark. It’s sexy. It lowkey makes me blush.

I hope you love Jack Gilbert’s The Forgotten Dialect of The Heart as much as I do. You can buy Jack Gilbert’s book, The Great Fires, here. Thank you for reading alongside me. If you enjoyed this, I hope you’ll share it with a friend and consider subscribing. Remember, I am hosting office hours next Wednesday, May 28th from 8pm-9:30pm EST. Bring a poem you want feedback on. Bring a poem you don’t get and want to read together. Bring questions about writing and poetry.

If you come up with any good metaphors for your joy, leave them in the comments. See you next week!

I love Jack Gilbert and this poem so much. Today my joy is a black hair tie around my wrist, whose garter has baconed. My joy is a long letter from a friend. My joy is a yellow fountain pen.

Wow I absolutely loved this. Thank you for the soft, wondorous world of reading poetry again. This healed a insecurity I have even as a poet reading poetry! I don’t have any academic background when it comes to poetry or creative writing. I met poetry in slam in chicago so when I started teaching I felt so incapable. But I started approaching it from what I do know and I feel better being at the front of the classroom. My students struggle with being wrong with reading poetry all the time so this is so medicinal thank you!